Culture and Society: Women in Culture

General

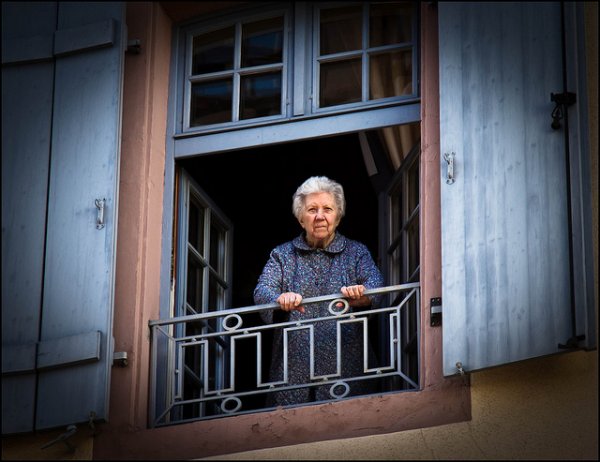

Historically, women had few legal rights and were rarely educated in France. Today, French women play a prominent role in the family and in society, and are usually treated as well as their male counterparts. Relatively minor variation in treatment depends on social and economic class. French women enjoy equality with men in status, education, employment, and in many other spheres. French society does encounter lingering patriarchal elements, but women have full freedom of choice.

Women’s participation in the employment sector proves greatest in retail, government service, academia, medicine, and service arenas. Participation in politics is increasing, and a constitutional ruling calls for every political party’s election list to include 50 percent females. Women hold about 40 percent of the seats in parliament. Increasing numbers of women occupy managerial or executive positions in business and more women are becoming business owners, taking up jobs in technology and other sectors. Almost half of all doctors in France are female. Nevertheless, there remains a wage gap between men and women of about 10 percent.

Women in rural areas, in some communities, and in certain regions still limit themselves to traditional women’s tasks, both in and outside the house. Though rural women often enjoy less status, their economic activity rate has matched that of urban women since the end of the 20th century. Many of France’s African subcultures place more social restrictions on women. These women are more likely to be discriminated against when applying for work outside of their own communities.

In terms of dress, French women have been stereotyped as some of the best-dressed in the world, and in fact, no restrictions on women’s dress exist in France.

Legal Rights

French women won the right to vote in 1944 and have equal access to elected posts. Laws protect them against discrimination, violence (including marital violence and spousal rape), trafficking for sexual exploitation, and practices like female genital mutilation. Women enjoy equality in family law and property law, ensured by the Ministry of Parity and Equality. They have the right to drive, can own, manage, and inherit property independently, and can make their own reproductive decisions.

Women can initiate divorce, which is granted on three grounds: mutual consent (by joint request or initiated by one spouse and accepted by the other); irretrievable breakdown of the marriage; or fault. Both partners have equal rights towards joint property after divorce in most cases. In divorce cases involving children, courts require both parents to contribute towards the children’s maintenance. Courts usually award joint custody, and in cases where they do not, the non-custodial parent receives visitation rights, provided no extenuating circumstances interfere.

Education

Education remains free and compulsory for all French children, male or female, between the ages of 6 and 16. Schools and colleges are coeducational. The literacy rate for both females and males stands at 99 percent. French women with equal access to education, in many cases, prove better qualified than their male colleagues. More women than men complete the undergraduate level of education, and numerous women and men virtually demonstrate equality at post-graduate and Ph.D. levels.

Women still face discrimination while applying for jobs, especially when seeking high-level positions, regardless of their equal or even higher educational qualifications, according to some sources. In terms of pay, women consistently earn less and experience a higher rate of unemployment than men. As far as presence in the workforce, 51 percent of the French work force is female, but far fewer private-sector executives are women. Many women take to part-time and contractual employment due to a greater burden of balancing work and family life. Women hold the majority of France’s lowest-paying jobs.

Dating, Marriage and Family

French women choose their own mates; however, marriage rates continue to decline in France as more people choose socially and legally accepted live-in relationships. Forced marriages remain a problem in some ethnic communities, but French law stipulates that parents be prosecuted if they force a child to marry.

Young women may date, and sometimes begin dating as young as 12 or 13. They may meet their future spouses in a wide variety of ways, but most French women marry men from the same region as themselves. Average age for marriage is 28 for women and 30 for men, though regional and class differences play a role in marriage age.

Women generally assume their husband’s name after marriage, though no requirement necessitates this. A recent French law allows children to be given both their mother’s and their father’s surnames. In cases of divorce, a woman usually reverts to her maiden name, though she can keep her married name through mutual agreement or by obtaining a judge’s authorization.

Married women generally have equal say in household matters, though this varies according to their social and economic status, by region, and even according to ethnicity. Married women also have the right to own and manage property independently within a marriage. The French generally attach no stigma to not having children or to having few children. In France, the birth rate has reached 1.87 children per woman, the highest in the European Union.

France banned polygamy in 1993, but some African communities still practice it. French authorities work to discourage the practice, but most polygamous marriages take place overseas or predate the 1993 law.

Health

Women have equal rights to medical care in France and have a long life expectancy. Standards of medical care prove excellent, and the infant mortality rate remains low, at approximately 4 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Women can make their own reproductive and health care decisions and France was the first western country to introduce the RU 486, a medication for bringing about an abortion.

Statistical sources include:

Inter-Parliamentary Union, Women in National Parliaments

Copyright © 1993—2025 World Trade Press. All rights reserved.

France

France